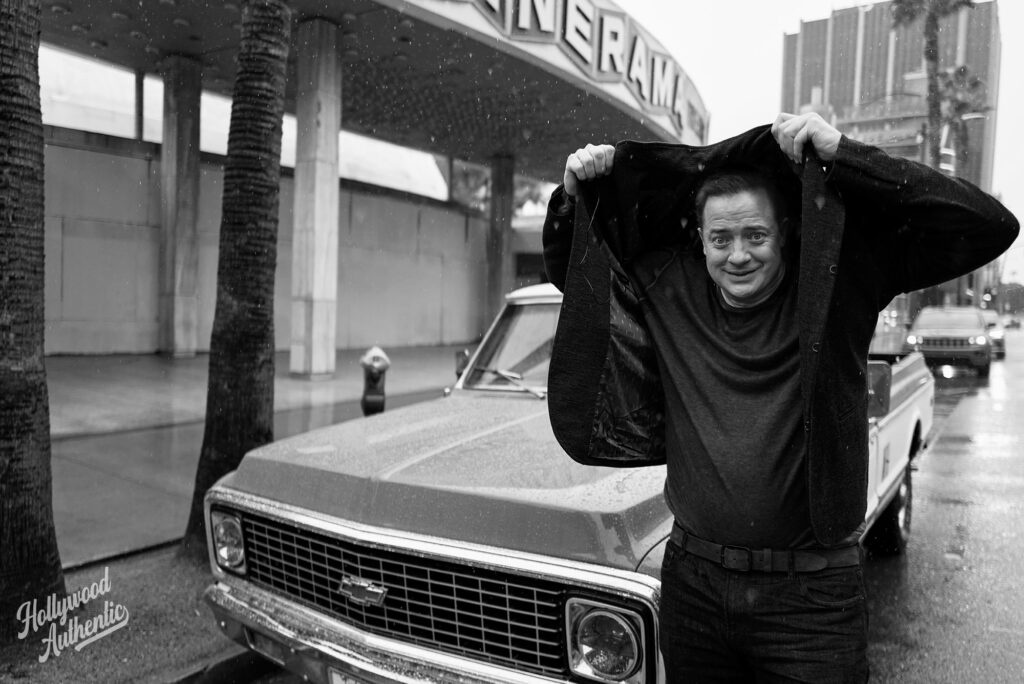

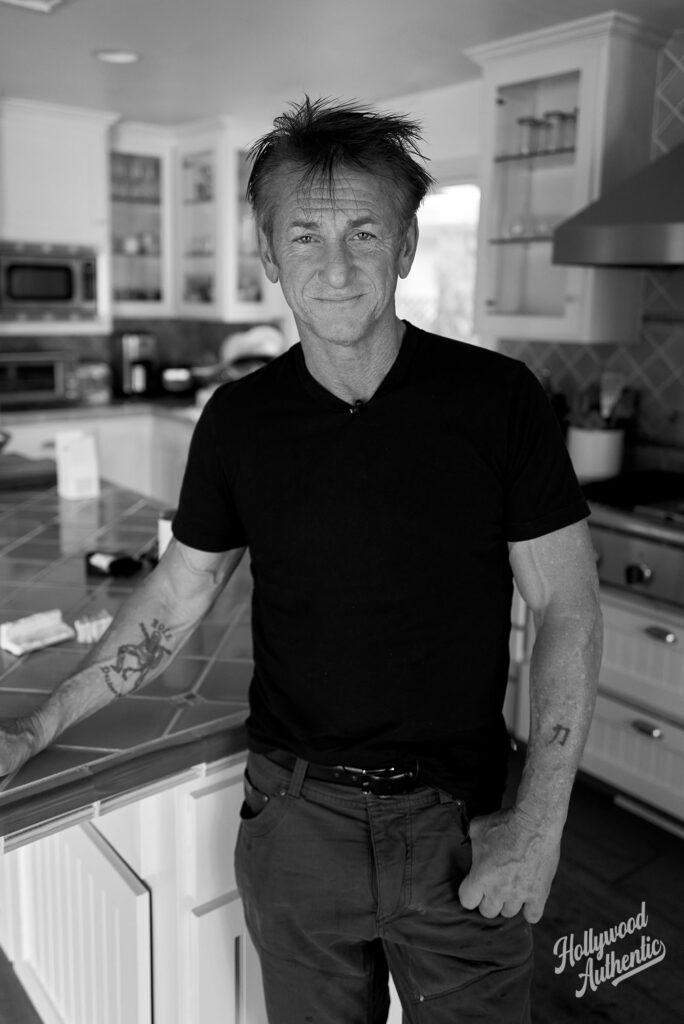

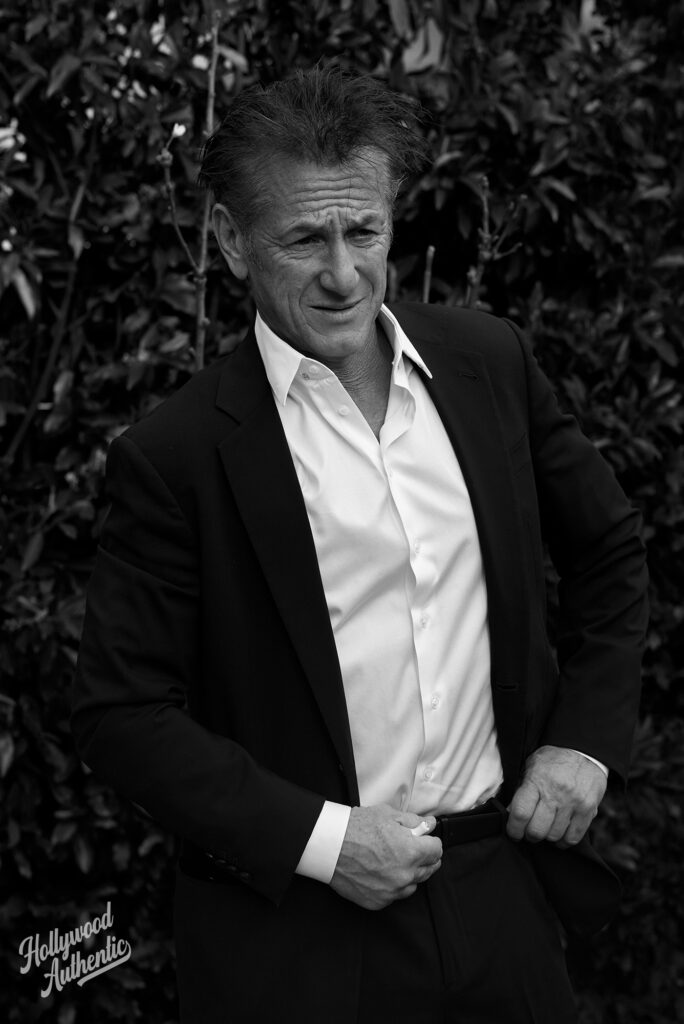

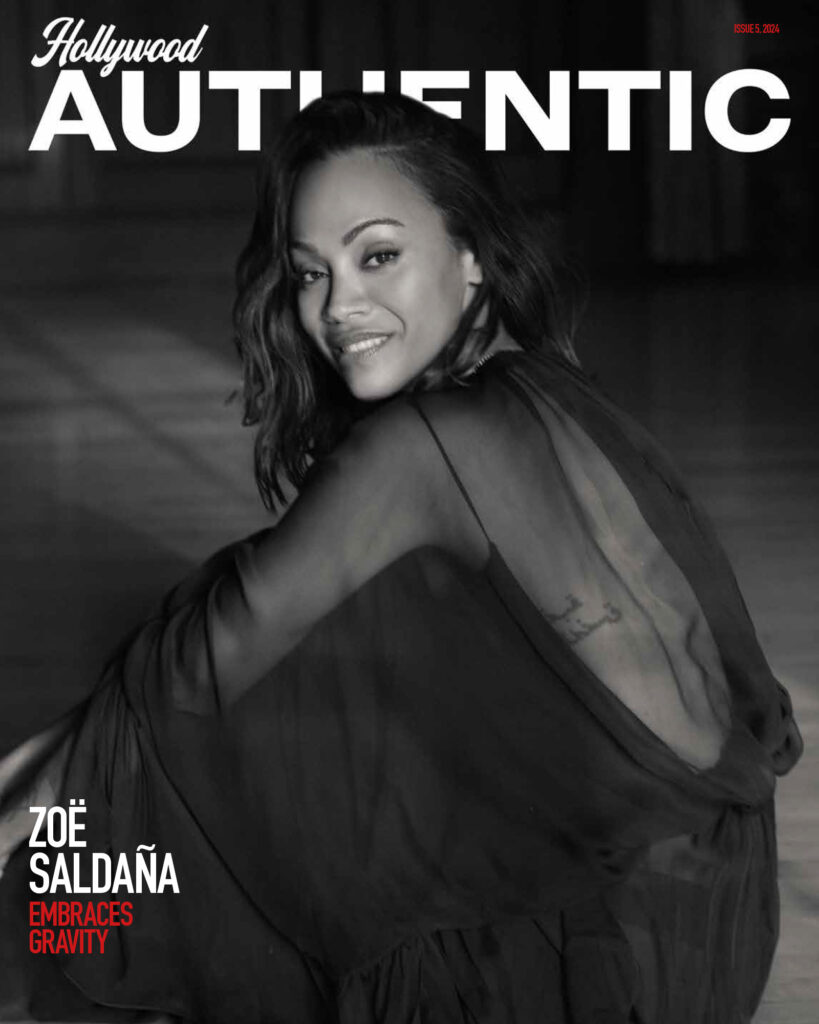

Photographs and interview by GREG WILLIAMS

As told to JANE CROWTHER

I’m an island girl. I need to always be close to the water,’ says Zoë Saldaña. ‘As a kid in New York and the Dominican Republic we always went to the water. We always walked on the beach.’ I’ve come to meet Zoë a couple of hours up the coast from LA. She loves the area, promising me that the place ‘compels you to relax’. Downtime is something she takes seriously as she juggles her career and home life with three lively kids, a dog, a cat and two goldfish. We meet at the picturesque El Encanto Hotel in Santa Barbara and her husband of 11 years, artist and filmmaker Marco Perego Saldaña, and her goldendoodle, Dolce, are also waiting with Zoë when I arrive. ‘I feel that this is a part of California that if you never get to go to Portofino in Italy but you come here – then it’s OK, you’re not missing much,’ she says as she welcomes me. ‘This bay area is so beautiful. Everything slows down. And you hear the wind in the trees, and the water. You smell different smells of life. It compels you to choose different thoughts.’

Born in New Jersey to a Dominican dad and Puerto Rican mom and growing up in both New York and the D.R., she now calls California home. ‘In New York I had the metropolis sounds of a city, the culture and access to the world just block by block. You can taste the world and hear the world,’ she says over coffee as we sit on a sunny terrace overlooking lush vegetation. ‘And then in the Caribbean, there was just sun, salt water, family and music – it was great.’ We take a walk with Dolce (full name: Dolce Vita Perego Saldaña), who Zoë soothes with whispered affection. ‘Beso, beso,’ she murmurs, kissing the pooch.

You reach a point in your life that time comes knocking, and says, ‘Hey, you’ve got to pay attention to this. You can’t miss any more moments with these people that are special to you’

Ballet was, she says, initially a way to cope with the move from New York to the Dominican Republic at the age of 10. ‘I was having a hard time making and keeping friends, finding my place, and feeling seen and understood. Even though it’s where our family is from, it was a big culture shock for us. Change is always new and scary at first. And my mom just took me to a ballet class…’ Zoë tells me she found the almost militant nature of training both a comfort and a challenge. ‘There was something about ballet and the bar – my teachers were so rigid and strict. And yet they were like true champions of the progress, effort, determination and sacrifice that I had to make and it became an obsession. It became my cave for 10 years of my life. I never felt that I really mastered it because I never got to be a part of a company, or be the prima ballerina, and I never got to dance in Romeo and Juliet or The Nutcracker. So I always felt like I had failed. After reading Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell, I realised that I did put in 10,000 hours in the span of 10 years. So I did become a master at ballet. Whether I was recognised for it or not, it doesn’t take away the fact that I did it.’

The ballet might not have become a vocation but it did lead to acting after the family returned to NY, with the then 22-year-old getting cast as a dancer for her first screen role in Center Stage in 2000. ‘I never had any formal training when it came to acting. But ballet gave me this connection to my body that I was able to use in those roles I was more qualified for.’ That led to acting opposite Britney Spears in Crossroads, having her first taste of a franchise with Pirates Of The Caribbean: The Curse Of The Black Pearl, inhabiting an icon in Uhura on JJ Abrams’ Star Trek series, bending the limits of CG with Avatar, kicking ass in Colombiana and joining the Marvel stable as green-skinned Gamora in the Guardians Of The Galaxy and Avengers films. Her work on both Avatar movies (with three more incoming) plus Infinity War and Endgame have made her the industry’s highest-grossing actress, and a sci-fi fan favourite. ‘I love science-fiction. I love action. And I love being able to incorporate what I can do [as a ballerina] into that.’

She is currently reading Nicole Avant’s book Think You’ll Be Happy: Moving Through Grief with Grit, Grace, and Gratitude and we discuss the idea of being present and embracing who we are now. ‘My folks are getting older, which hints of time passing and being this invaluable luxury,’ she says. ‘We spend a portion of our lives taking that for granted, we think it’s always going to be there and we’re always going to have time. And then you reach a point in your life that time comes knocking, and says, ‘Hey, you’ve got to pay attention to this. You can’t miss any more birthdays. You can’t miss any more moments with these people that are special to you.’ You’re born a daughter. You’re born a sister. And then as time goes by, you’re a wife, a mother, a professional. You acquire all these titles in your life. And then throughout life there’s this shift where you lose these titles over time. Nothing will ever change the fact that I’m a daughter, but the nearness of death becomes really present when you become older. So vacillating with that conversation is what I want to do. I don’t want to be afraid of it. I want to normalise it in my life, because I want to accept it.’

I feel like a diamond now for the first time in my life. When I was being called a diamond, I felt so insecure. I was so unhappy. Now I feel a different strength, beauty, and curiosity

I ask about her fears. As an actor, as a parent, as a daughter. She pauses. ‘We describe children as fearless. They bang themselves up, fall – then they’ll just get up and try it again. And that’s one thing that we lose when we become older. We become so self-aware of our vulnerability and fragility. And all of a sudden, that fearlessness becomes just fear. I’m learning to make peace with that so that I don’t become this rigid person who becomes so afraid that I stop doing things. There’s so much more I have to do. But I just have to let go of the things that I did, that maybe I won’t be able to do at the magnitude that I was doing them. Tapping into the fact that that’s OK – it’s bliss.’ She laughs. ‘But it comes and goes. There are days in which I wake up, and I’m just like, “fuck, I’m old!” And then there are days in which I’m like, “This is great!”’

Maturing in Hollywood requires a certain fortitude, particularly for women. Halle Berry and Sarah Jessica Parker have recently been unapologetic about ageing and Zoë is cognizant of the tightrope women in the public eye have to walk. ‘I picked a medium in art that relies a lot on the visual – how young you feel, how young you look,’ she says. ‘You get so used to it and it becomes a bad habit where you sometimes spend all of your time thinking about how you look, and not enough time thinking about how you feel. I think we have to talk about that more. There’s so much more to women than their looks and youth. I find women beautiful when they’re five, and when they’re 95. In Hollywood, women are viewed like diamonds when they’re super-new and super-fresh. I feel like a diamond now for the first time in my life. When I was being called a diamond, I felt so insecure. And now I feel a different strength, a different beauty, a different curiosity. I’m ignited by other qualities besides my looks. And those people who see that in me now become so much more meaningful to me.’

I dig into memories to help me transport. I write all over the script, give the role an animal and substitute the characters for somebody I know

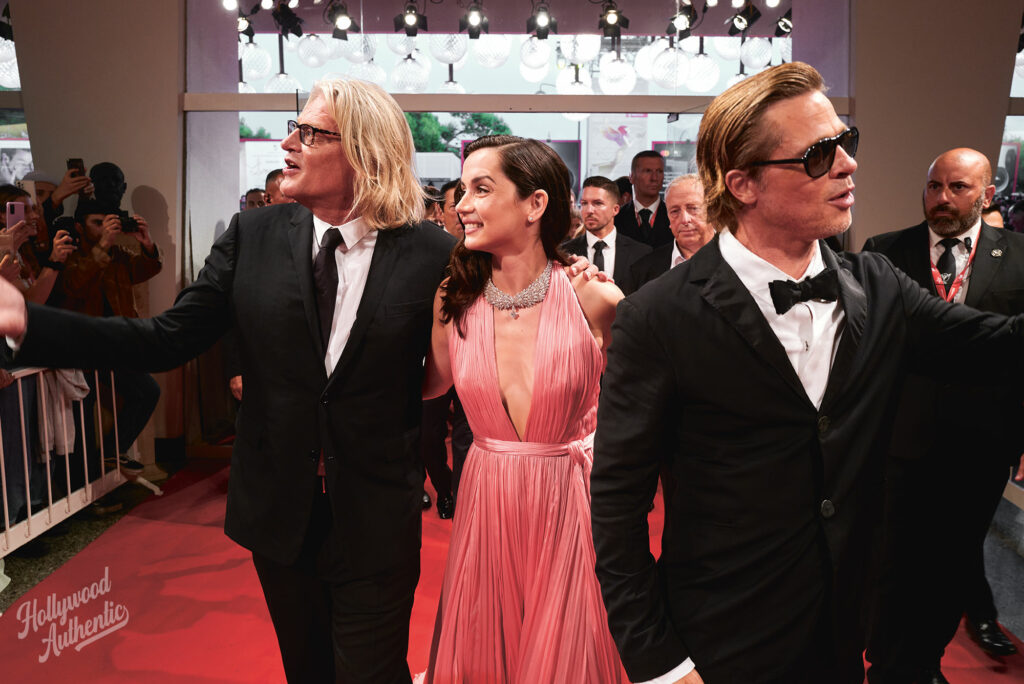

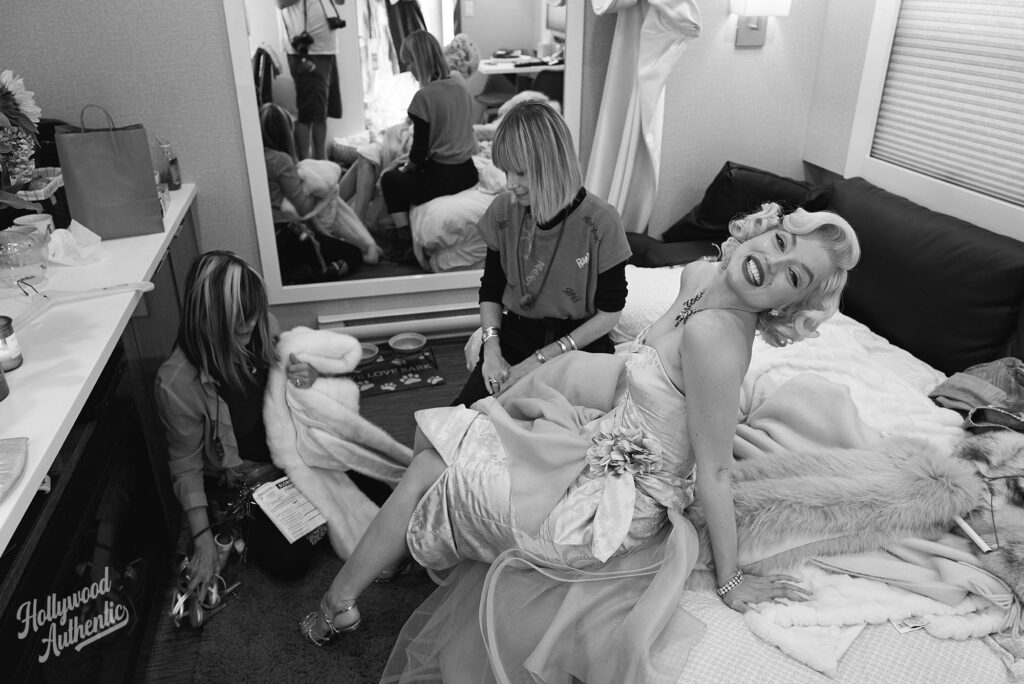

We jump in her car and head for the beach. I want to go back to Zoë’s declaration that she has so much more to do. Her future projects include three more Avatar movies with James Cameron and more Star Trek. But first up is a project with Jacques Audiard that taps into her heritage and her dancing background, Emilia Perez. Billed as a musical crime drama, the picture follows a female lawyer in Mexico as she helps a cartel boss evade his enemies and become the woman he’s always wanted to be. Though Zoë has sung on a film before (most recently in animation Maya And The Three) she has never sung in Spanish or on screen. ‘I’m going back to my roots. I’m singing, and I’m dancing, and I’m doing a role in my native tongue,’ she enthuses, admitting that working with Audiard has been something of a dream since she saw The Beat That My Heart Skipped in a movie theatre in NYC in 2005. ‘I remember thinking, “I want to work with this director.” And the fact that I manifested it and then met Jacques Audiard and got to know the whole premise behind Emilia Perez, and the challenge that he was proposing of whether I was going to sing and dance… I was like, “OK!”’

Audiard’s method of working with the same crews is also something Zoë embraces. ‘I like directors that are known in their field for being super-loyal to their people, because I love the crew. They become family to me. They’re the ones that I truly look up to. They’re so unconditional. They’re wonderful people. And whether I’m working out of the UK, New York, Los Angeles or Paris there’s a universality to crew people. They’re decent and they’re hard working.’

Part of the crew on Emilia Perez was famed choreographer Damien Jalet, who put the actress through her paces on a big dance number. ‘If Damien would tell me, “It’ll take you seven hours to learn this,” I would double it. I’d need 14. I’m also dyslexic, I have ADD and I suffer from anxiety. I like to take my time with things. That way it becomes a muscle memory and I force myself to be out of my head. But it was an experience, and I loved it. When you’re a child that has a lot of trauma, and you grow up, and you’re constantly in conflict – as an artist, you’re made to believe that in order for you to be great, you have to be chaotic, and you have to live in conflict. It just becomes so exhausting.’

Zoë lost her father in a car accident when she was nine, the tragic catalyst for her and her two sisters’ move to the Dominican Republic. ‘When you learn to deal with grief at a very early age, it lives with you. It doesn’t go away, you manage it. And every now and then it comes up. If I hear the song Gravity by Sara Bareilles I always think about my mom and dad, because when he passed away they were not in a good place in their marriage. We didn’t have proper closure. I spent so many years thinking of what could and should have been. I never got to see them mature together. And that’s why the Dominican Republic was this bittersweet place, because it is paradise. The food, the people, the culture, the history – I love being Dominican. It’s just so powerful. And yet the reason why, and how, we got there was sad.’

I hear my grandmother’s voice every time I see my children sleep, and I pray over their little, sleepy heads, just like she did, just like she taught my mom to do. That’s a legacy I want to be. That’s immortality

As her now-single mom picked up the pieces of their shattered lives, Zoë recalls the impact her maternal grandmother made on her life. ‘My grandmother was always there. It was always us five – my sisters, myself, my mom, my grandma. It was great! It’s funny, my grandmother prayed a lot, and when she died [in 2019], the prayers stopped.’ Now, she says, she finds herself doing all the things her grandmother used to. ‘Everything that she told me to do my whole life that I would roll my eyes at! I hear her voice every time I see my children sleep, and I pray over their little, sleepy heads, just like she did. That’s a legacy I want to be. That’s immortality.’

We get out of the car and head to the beach below. An invigorating wind blows off the ocean, whipping Zoë’s hair as she leaps along the sea wall. This is a cinch for an actress who did months of parkour, archery and combat training for Avatar – and breath-holding for underwater worlds in Avatar: The Way Of Water. The physical discipline of it tapped into her balletic sensibilities. ‘I’m addicted to seeing myself do things that are unimaginable. For example, in theory, someone will tell me, “You’re going to follow these exercises, and you’re going to hold your breath for five minutes if you want.” I’m like, “Get the fuck out of here!” she says. ‘And all of a sudden, every time you do it, it’s three minutes, four minutes, five minutes… And then you find yourself doing it on your own time and teaching your kids to do it. They are dolphins, marine animals. And it’s particularly important to me because being an island girl, we all had to learn how to swim. You come out of the water, and you go back into it.’

As she dances on the sand, her coat billowing behind her and pelicans flying across the water, I ask what she next sees herself doing that is unimaginable? “I would love to do a comedy – I only just did my first romantic series From Scratch in 2022. Before that I’d never been in a romance besides one that’s between two worlds when aliens are coming for you!’ I ask her about the fact that she is now, according to Wikipedia, the highest-grossing actress in the world. ‘I can’t grasp it,’ she says. ‘I can’t conceive of it. So all I keep doing is repeating what I’ve been told my whole life: be grateful. I know what it’s going to mean to so many young girls or boys out there who feel like they don’t belong, and they’re trying to find their place. Somebody did before you did, so that means you can, too.’

That doesn’t mean she’s invincible. Later, as we return to the warmth of indoors and a rehearsal studio, Zoë applies an ice pack to her knee. ‘This is the acceptance of my physical limitations,’ she smiles. ‘And learning to love my body as it is now. It’s a crazy, beautiful time.’ We return to the subject of gravity – something she seems to defy in her roles but that she’s now feeling and welcoming into her life. ‘I now feel the floor. When I used to dance, I didn’t feel it. My teachers would say, “Use the floor.” And I couldn’t because I was always jumping higher. You would do your grand jeté across the room, and then I would run back, because I couldn’t wait to do it again.’ That rigour is still a part of her acting practice. She’s worked with the same acting coach for over 20 years and breaks down roles in the same way she did when starting out. ‘I dig into whatever memories I have that may be similar that help me transport. I write all over the script, and I give the role an animal, I substitute the characters for somebody that I may know. Other times, it’s just endless conversations with the director, creating a very vivid backstory for the character – so much so I’m getting air in her lungs. For instance, the film that I did with my husband, The Absence of Eden, I play this woman who is undocumented. She feels like she has no choice but to flee her situation in Mexico and cross the US border. I didn’t want to do this technical research on the politics of how we feel about immigration. I felt the character is not right or wrong. She’s just scared, hungry and lonely. She is loyal. She’s the things that felt familiar to me. For Rita, the character I play in Emilia Perez, she’s so invisible. And that invisibility has turned into resentment. We’ve all experienced events in our lives where we have felt really strong, strong feelings and I channel that. It was incredibly enriching to play someone like her.’

‘One time, a really good friend gave me a critique that I wasn’t ready to hear, but I’m so grateful that she said it. She said, “I can’t wait for you to lower this guard down. You’re such a guarded actor,” And when I heard that I was taken aback, but she was right. I can’t watch myself. There’s nothing I do that I like. I like the movies. I love what everybody else does. I love the choices the director has made. I don’t like the way I carry out things. When I sit through a premiere and watch myself I’m cringing. I’m sick to my stomach. I think it’s because I just don’t want to deal with the fact that deep, deep down there’s always going to be that dancer in me that doesn’t think I’m good enough. That I just got here by chance.’

Zoë sits for a beat and processes this self-criticism. ‘There is a simple compromise though,’ she says. ‘Just do what you want. There are so many projects that I should do right now, but there are so many more I want to do. I’m going to see if by following that desire versus duty, that one day I will be able to sit through a whole thing that I’ve done, and enjoy it along with everybody else.’

Photographs, words and video by GREG WILLIAMS

As told to JANE CROWTHER

Zöe Saldaña stars in Emilia Perez which opens in Cannes. By Saint Laurent Productions, Why Not Productions, Page 114 and Pimentia Films